by Chris Poggiali & David Konow

Like numerous low-budgeters released by Independent-International Pictures (IIP) during the 1970s, Al Adamson’s blaxploitation thriller MEAN MOTHER started out life as a completely different film. EL HOMBRE QUE VINO DEL ODIO (1970) was the source, a Spanish/Italian co-production about European jewel smugglers, starring Italian sex symbol Luciana Paluzzi and Canadian actor Lang Jeffries, and directed by León Klimovsky (who is best known today for making a string of horror movies with popular Spanish fright film star Paul Naschy, a.k.a. Jacinto Molina).

Klimovsky’s film somehow made its way to the U.S. and landed on the desk of Samuel M. Sherman, president of IIP, who had no idea how to properly market a dubbed European crime movie at a time when “blaxploitation” films were the current rage. The eyes and ears of Hollywood were tuned in to the incredible box-office receipts of Melvin Van Peebles’ low-budget sensation SWEET SWEETBACK'S BAADASSSSS SONG (1971), now considered to be the first shot fired in the enormously popular black cinema movement of the early ‘70s, and exploitation producers like Sherman were scrambling to cash in on this fad.

“My wife Linda and I were always looking around for different actors,” Sherman explains, “and we had seen Fred Williamson early on in a picture with Liza Minnelli called TELL ME THAT YOU LOVE ME, JUNIE MOON (1970), directed by Otto Preminger, and we really liked him. 'This guy is good,’ I said. ‘Someone’s gotta discover him.'” That someone turned out to be Al Adamson, IIP’s number one in-house director, who was developing a black version of the 1947 classic BODY AND SOUL with a screenwriter named Charles Johnson. The film was to be called BJ, after the lead character’s name, but that changed once Fred Williamson signed on to the project. A former defensive back for the Oakland Raiders and the Kansas City Chiefs, Williamson was nicknamed “The Hammer” because of his powerful forearm, and the tremendous force with which he would use it against his opponents.

Says Sherman, “I think Al, once he met with Fred Williamson and knew he was going to be in it, thought to tie the two together and call the character BJ Hammer.” The film itself was eventually renamed HAMMER and released by United Artists, but by that time, Sherman was no longer involved with the project. “It was something that started with us at IIP, but I didn't want to go further with it because I saw it as a bigger budgeted film. I didn't see the need to spend that kind of money. I didn't think we could afford it, so Bernard Schwartz made it – the same man who eventually made COAL MINER'S DAUGHTER.”

At some point during the production of HAMMER, Sherman and Adamson came up with a crazy plan to transform EL HOMBRE QUE VINO DEL ODIO into a black action film, “even though it seemed far-fetched, since it didn't have those elements to begin with – just like DRACULA VS. FRANKENSTEIN, which began with no Dracula and no Frankenstein!” Sherman says with a laugh, referring to one of IIP’s most famous patchwork films. Over the 30-plus years that he has been distributing movies, Sherman has become quite an expert in the area of film reconstruction, having supervised such IIP patch-up jobs as NURSES FOR SALE (1976), BEDROOM STEWARDESSES (1978), DOCTOR DRACULA (1980), and EXORCISM AT MIDNIGHT (1981), to name just a few. “It’s all based on one thing, and that’s editing,” explains Sherman. “And being that I started out as a film editor, I understood that editing is just assembling a mosaic of little pieces into a patchwork quilt. You can change anything just by how you edit it and how you put the sound in.”

“There are several means of redoing a movie,” he continues. “One, you can put a framing story around the existing story. That would be like what we did in HORROR OF THE BLOOD MONSTERS (1970), where we did the story with John Carradine around the cavemen footage. Another way is to integrate new material into already existing footage, which is very difficult to do. You have to recreate the sets, make-up, photography, lighting... I did that when we shot new material for THE CREATURE WITH THE BLUE HAND, which became THE BLOODY DEAD. And a third way is to do parallel construction – when you have a second story going on at the same time as the main story, and you cut back and forth between them. That works, as long as you pull the stories together at the end with some crossover footage, where the characters from the two stories meet and bring the audience up to date on what they’ve been doing.”

Sherman and Adamson decided that parallel construction would work best for the Klimovsky film, and HAMMER writer Charles Johnson was called in to work on the new plotline. “The Vietnam crisis was going on at the time, and it involved soldiers of all ethnic backgrounds,” Sherman reveals. “So the idea was that if we started the picture [in Vietnam], we might have a tie-in to a parallel story with a black co-lead who could also be in Vietnam, and that would enable the picture to move sideways. That would be the parallel plot.”

If leading man Clifton Brown looks familiar to lovers of ‘60s and ‘70s pop music, that’s because he’s actually Dobie Gray, singer of the Top 40 hits “The ‘In’ Crowd” (#13 in 1965) and “Drift Away” (#5 in 1973). Gray was no stranger to pseudonyms; born in Texas as Lawrence Darrow Brown, he has also been credited as Leonard Victor Ainsworth, Larry Curtis, and Larry Dennis on various music recordings. When his singing career fizzled in the late ‘60s, Gray went back to college, performed lead vocal duties for a hard rock band called Pollution, and pursued an acting career. He played Billy the Kid in the New York production of Michael McClure’s controversial play “The Beard” (directed by Rip Torn) and appeared in the Los Angeles production of “Hair” from 1968 until 1972. It was during that lean period shortly before the recording of his classic hit “Drift Away” that Gray became “Clifton Brown” and entered the blaxploitation history books as Beauregard Jones, the “Mean Mother” – his only dramatic movie role, as far as we know. Sherman and Adamson, always quick to cash in on a star’s success, somehow missed the perfect opportunity when “Drift Away” hit the charts in April of ’73 and stayed there for 15 consecutive weeks. (Gray passed away in December 2011)

Marilyn Joi was an exotic dancer at The Classic Cat, a bottomless club in Hollywood, when Adamson first approached her with an offer to be in movies. She agreed, and appeared in HAMMER as “Tracy-Ann King,” performing a sexy nightclub strip for Fred Williamson and co-star Vonetta McGee (Tracy-Ann King was one of several names Joi used while touring the strip club circuit – note the initials, T and A). Adamson elevated her to leading lady status when he cast her in the new parallel plotline footage for MEAN MOTHER. “When I first saw the footage of her,” Sherman says, “I said to Al, 'I like her! She's really good, she’s really pretty, she's willing to do nudity – let’s keep using her.'” The gorgeous starlet would go on to do several other films for Adamson: THE NAUGHTY STEWARDESSES (1974), BLAZING STEWARDESSES (1975), BLACK SAMURAI (1976), NURSE SHERRI (1978), and another patch-up job, UNCLE TOM’S CABIN (1976).

Al Richardson was also recruited from HAMMER to liven up the new parallel footage, and he too would go on to make more pictures with Adamson and Sherman, including THE DYNAMITE BROTHERS (1974) and BLACK HEAT (1976). “I enjoyed working with black actors,” states Sherman. “Al [Adamson] and I were on the same wavelength about this, and [IIP vice president] Dan Kennis agreed that we should have black actors and actresses in everything. It wasn't a question of making movies to appeal to strictly black audiences in the big urban markets. We knew the blaxploitation films were going to be a trend that would come and go, like any trend. But we felt that the cast should be reflective of the make-up of people in the world. I wanted Al [Richardson] in THE NAUGHTY STEWARDESSES because of his performance in MEAN MOTHER, and he ended up having some of the best scenes in that movie.”

A third “Al” – Albert Cole – also turns up in the parallel footage, and had already appeared in four Adamson productions: THE FEMALE BUNCH (1971), DOOMSDAY VOYAGE (1971), DRACULA VS. FRANKENSTEIN (1971), and ANGELS’ WILD WOMEN (1972). However, he’s probably best remembered for playing the psychopathic head that Bruce Dern grafts onto a retarded handyman’s body in THE INCREDIBLE TWO-HEADED TRANSPLANT (1971). "I met him before [that] was a finished movie,” Sherman says. “[Producer] Tony Lanza only had a preview reel, about ten or fifteen minutes, and he was trying to expand that into a full-length movie. So I met Al Cole when he was the head! Whenever I'd see him I'd say, 'There's the head!' Being a guy from New York like me, we hit it off."

According to Sherman, the construction of the new film took many months. “We started doing it under the title SOUL BROTHER, and since I disliked the original film, we kept getting rid of the old footage and shooting more and more new footage. As I'd see it edited together, I'd say, 'Go further – we’ll spend more money – we’ll cut this out…’ Sometimes it can cost more to do it this way than it would if you just made a picture from start. At least that way you’re not working around material you already have, which limits you in a lot of ways. You have to do certain things you wouldn't have to do if you just wrote a whole new script."

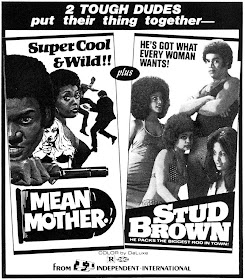

Once the film was completed and the publicity campaign was in place, MEAN MOTHER quickly found its niche. "We went where the audiences were known to be – the big cities, major urban areas, where a lot of the big downtown theatres had thousands of seats and were appealing to African-American audiences. Philadelphia, New York, Detroit, Chicago, Los Angeles, St. Louis, Atlanta, Memphis – these cities had large African-American populations, and [theater owners] were happy to have product that could bring in a large attendance."

MEAN MOTHER was eventually credited to two directors, Klimovsky and "Albert Victor.” Sherman still isn’t sure why Adamson took the pseudonym. "Sometimes these things are lost to antiquity,” he sighs. “I have a pretty good memory, if you listen to some of the commentary tracks I’ve done. I even amaze myself with some of the things I've remembered, but I guess I could have forgotten an equal amount.” One possible explanation for the pseudonym is that Adamson was paying homage to his late father, Victor Adamson, who acted in cowboy movies under the name Denver Dixon. According to Sherman, the elder Adamson had been responsible for a similar patch-up job of his own back in 1934. “He was producing a serial called THE RAWHIDE TERROR. Somebody put up the money, they shot two chapters, and the leading man quit. Denver had this footage, and it was going in one direction rather than another, so he re-shot the thing, took the guy who played the sheriff, and made him the lead for the rest of the new footage.”

Independent film companies ranging from New World and Audubon to Aquarius and Olympic International were known to incorporate new footage into their finished films from time to time, but Sherman’s studio is the one most associated with this process – to the point where many genre fans consider IIP to be little more than a schlock movie chop shop. “I was always of the opinion, waste not want not,” says Sherman, who’s quick to point out that major studios also practiced the patch-up technique. “The piecing together of pictures is as old as the industry itself. Irving Thalberg, the head of production at MGM, was notorious for shooting a film, hating it, throwing two thirds of it away, re-writing it, and re-shooting it in another direction entirely. They used to say at MGM, 'Great movies are not made, they're remade.'"

Excellent!

ReplyDeleteSimply FANTASTIC article here.

ReplyDelete